In praise of slowness

I embroidered a question on the trousers of my suit this morning: ‘What is progress?’ The progress of my suit is that it is slowly being covered in questions. ‘What if there is no tomorrow?’ ‘Do peppers grown in space taste better than peppers grown on earth?’ ‘Is standing still the best way forward?’

The suit isn’t as sharp as it once was. More than six months of wearing it daily wherever I went, washing it regularly, doing things that left stains I couldn’t remove, made it look worn. But that was the whole point.

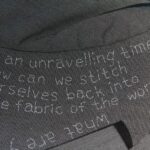

‘In an unravelling time, how can we stitch ourselves back into the fabric of the world?’

When I wake up and get dressed I don’t need time to think about what I am going to wear. I put on the suit, like I did yesterday and the day before, and the days before that. Then I go outside and check on the plants. The ones that aren’t there yet but I know will come out of the earth soon. The trees that have no leaves yet but show the first buds. The seeds I planted, even though I know it will take a few more days before the green shoots have wrestled through the thin layer of soil. The changes happen slowly, even when the optical change is a sudden one, when overnight a flower has opened on a cactus, when dead tree trunks are suddenly occupied by dozens of oyster mushrooms. Sometimes little has changed, but I enjoy the anticipation of what I might see, the knowledge that there is something in the making even when I stare at a barren field.

I make coffee and write a friend a whatsapp message. ‘How are you?’ I ask. ‘Working still’ he replies straight away. ‘Busy as usual’. I consider writing to him again, repeating the question he hasn’t answered but I don’t. Some people get their identity out of always being busy and in a way he did answer my question: to my friend being busy means being productive means doing well. Or it might mean ‘I don’t have time to think about how I am and maybe that is for the best.’

It was tempting to write ‘Busy here as well’ but I wouldn’t mean the same thing. I would mean my mind is occupied most hours of the day by a creative process that asks for unproductiveness in the capitalist sense. Kazimir Malevich, Polish-Ukrainian Russian avant-garde artist and art theorist said: ‘there is no art without laziness’, but I wouldn’t call it that, I would call it attentiveness, or an attentive waiting.

Living is a slow process. In every day there are 86.400 seconds and just as many, maybe more, moments. Every moment is a world in itself. We aren’t present in the past or in the future, we are only present in the moment. Everything else exists only as memory or expectation, trace or anticipation. When you are young you want to live fast, you yearn to be older, to have the freedom to make your own choices. Then there is the time when it seems to go too fast, when you become aware of your mortality. Apparently when you are old, older, it changes again, maybe because you have to live slower again, maybe because there is more to remember.

‘Do you think I need wings?’ The last time I was flying I asked for a window seat on the left side of the plane, knowing I would be able to see the sun setting almost indefinitely, flying north. The view always softens the slightly soul-crushing experience of leaving a place at a pace that is confusing if you are attuned to the speed of your body. There were three things that struck me. The first was how the ornamental grasses in the outdoor waiting area softly waved in the wind in a hypnotising movement. The second was the young boy sitting next to me in the aeroplane, tapping my shoulder to ask if I could close the window because the sunlight coming in prevented him from playing his computer game. The third was, looking through the now half closed window at the world from a completely different perspective, how slow the plane appeared to move although we were probably doing something like eight or nine hundred kilometres per hour. The endless surface of clouds looked so soft and fluffy that I was almost sure it would catch the plane gently if we should fall.

There is a piano piece by Alexander Knaifel, ‘In some exhausted reverie’, that starts with sixteen seconds of silence and then three single notes played with the ultimate concentration in the next fifteen seconds. After one minute, only fourteen notes have been played, every single one breaking the silence and being a whole world in itself. I remember hearing it for the first time on the radio, sitting at the table in my living room, wondering for a moment if there was something wrong with the speakers, and then that first note and how it paused the whole world around me. It isn’t the slowest musical piece that has been written – that is without any doubt John Cage’s ‘As slow as possible’, currently being played in a church in Halberstadt, Germany, and scheduled to last 640 years – but it is probably one of the slowest pieces I will ever hear.

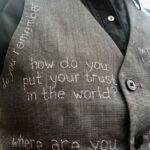

Most embroideries take at least an hour, the long questions might keep me occupied the whole morning. It is a slow process, I try to stay with the question while embroidering it, with the person who asked me the question. Some people send me questions through social media, others stop me when I am on my way somewhere or nowhere in particular to comment on the suit, and usually we get into a conversation that sometimes leads to a new question. ‘What does silence look like?’ a man walking his dog on the moor asked me after we discussed the absence of noise-free natural spaces in the Netherlands. I like that question, it is embroidered on the back of my trousers just under my belt. It is hidden most of the time, covered by the waistcoat and the jacket. ‘Where are the wild places?’ ‘They say we are running out of time, but if we change our approach to time, can we be in the world and everything in it in a different way?’

Making art is more about being able to be slow than it is about being creative. I never longed to be an artist, it is something you become, you do have to master something, but this something can be anything, it can ‘just’ be mastering the art of slowness. Rainer Maria Rilke once said it beautifully:

‘ …. a year has no meaning, and ten years are nothing. To be an artist means: not to calculate and count; to grow and ripen like a tree which does not hurry the flow of its sap and stands at ease in the spring gales without fearing that no summer may follow. It will come. But it comes only to those who are patient, who are simply there in their vast, quiet tranquillity, as if eternity lay before them.’

‘How do you put your trust in the world?’ ‘How to love?’ ‘Who am I?’ ‘How do you listen to non-human voices?’ ‘What do you hold sacred?’ ‘Do you know the way?’ There are so many questions that are hard to answer in words because they need to be lived and put into practice. If you rush through your life you won’t find them, you won’t even be aware of the questions.

‘How do you grow things?’ In nature everything has its proper time, rhythm, balance. When you try to change that, strange things happen. It doesn’t only apply to living organisms but to other things as well; ideas, relationships, trust, the world as a whole. This world of ours that isn’t separable from ourselves, that isn’t a fast place in itself: we don’t live in a fast world, we live in a fast society. ‘What is your neighbour’s name?’ So many people I met who read my suit realised they didn’t know.

I don’t have a favourite question but every time I sit down somewhere and cross my legs comfortably, I see ‘What if there is no tomorrow?’. I like that question because you can interpret it in two ways. On the one hand it reads like a memento mori: none of us are going to live forever, or at least not the way we are used to, in a human body that is inseparable from our brain. Would you have any regrets if you knew would know today was would be your last day? Are there things you haven’t done that are important to you? Did anything remain unsaid that should have been communicated? Did you live enough, love enough, enjoy enough, care enough?

But also: what if there really isn’t wouldn’t be a future? It sure looks like the human race is heading that way if there aren’t won’t be any major changes, if we don’t slow down. Some days it might be tempting to say it doesn’t matter because nature, the planet, will survive anyhow, and might even be better off without us. But we are here, now. We matter, in the same way every species that went extinct and we could have saved mattered. We are smart, but we are not wiser than the trees. the rivers, the birds, the insects. They are in no hurry, they don’t know there will be a tomorrow.

More about this project: www.asoftarmour8.blogspot.com

Published in Dark Mountain Volume 22, Ark